Latest Updates

By Rodrigo Beilfuss

•

January 28, 2026

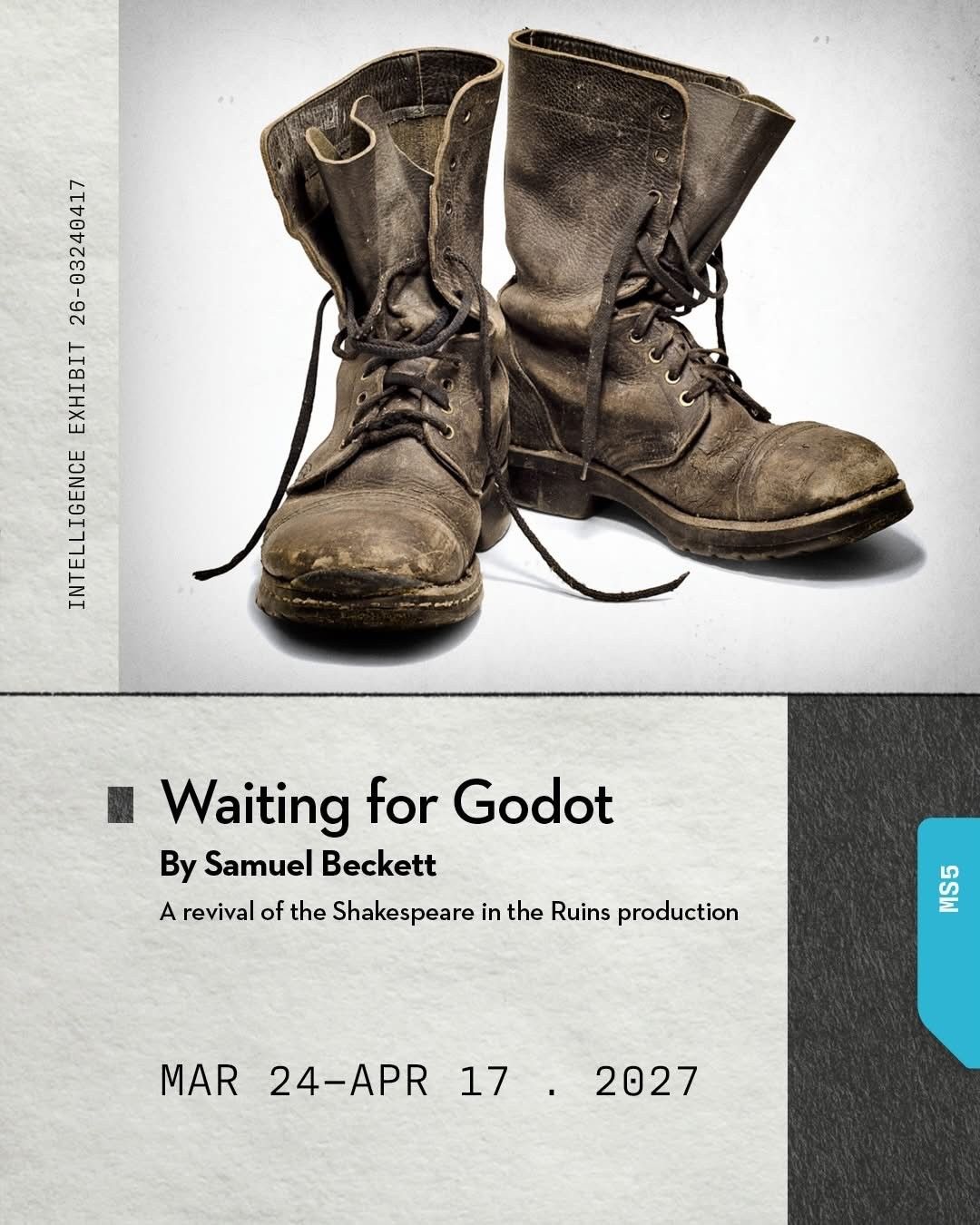

Dear friend, we have BIG news for SIR we’d like to share with you: Our 2025 production of Samuel Beckett’s WAITING FOR GODOT will be revived as part of the 2026/2027 Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre MainStage season! We are SO back! This is an exciting collaboration, and we couldn’t be more thrilled. As Estragon would say, “ What do we do now? Now that we are happy?!! ” The full stellar cast will be back, and we will re-imagine this stunning - and timely - text back to life, transporting the action from the outdoors and into the expansive indoor stage of the Royal MTC - what a great honour! I couldn’t be more grateful. Godot is my favourite (non-Shakespeare) play, and after the chaotic weather we faced at the Ruins last Summer, it is incredible to be given more life to explore this truly profound and delightfully silly play. ALSO, speaking of being grateful, I’d like to express how deeply moved I was by your generosity during our recent donation campaign - ‘Protect What You Love’. Your support is vital and brilliantly inspirational. THANK YOU ! 2025 was a challenging year, but also full of creation, daring, and love. We will be holding auditions this coming week, and in March we will announce our 2026 Ruins playbill - I cannot wait to share our plans with you! Here’s to the Future - our shared Future; we are your Shakespearean company. Lots of Love, Rodrigo , artistic director

January 2, 2026

Shakespeare in the Ruins is holding auditions for our 2026 outdoor production of “As You Like It”, with director Michelle Boulet and Artistic Director Rodrigo Beilfuss. Audition dates: January 26 & 27, 2026. Possible callbacks on February 12 & 13. Rehearsals begin: April 27, 2026 Performance dates: June 04 – July 05, 2026 The season will be officially announced to the public early in 2026. “As You Like It” will run in repertory with a solo Classical-adjacent show that has already been cast. Audition requirements: all roles in “As You Like It” are available, and actors will be asked to choose and prepare which ever of the sides below speak to them. Only one scene is required. Please state which character in the chosen scene you are reading for: – Act 1, Scene 3 Duke Frederick/Rosalind: Start Rosalind’s “Look, here comes the Duke” End Duke “…and in the greatness of my word, you die” – Act 3 Scene 2 Clown/Corin: Start Corin “And how you like this shepherd’s life, Master Touchstone?” End Corin “…and the greatest of my pride is to see my ewes graze and my lambs suck” – Act 3 Scene 2 Rosalind/Orlando: Start Orlando “Where dwell you, pretty youth?” End Rosalind “Nay, you must call me Rosalind. Come, will you go?” – Location/Time will be emailed when you book your audition. – FULL TEXT OF THE PLAY FOR REFERENCE: https://www.folger.edu/explore/shakespeares-works/as-you-like-it/read/ Please submit by Friday, January 16, 2026. Email your CV & Headshot AS ONE SINGLE PDF DOCUMENT, please, to Rodrigo at ad@sirmb.ca to express your interest. We appreciate all submissions but please know that only those selected for an audition will be contacted with an appointment. Priority will be given to members of CAEA. Artists must be able to work as Winnipeg-local. Thank you!

December 29, 2025

As we continue to celebrate what makes SIR and the people of SIR so special in our year-end campaign, we wanted to share with you a lovely conversation with LIAM DUTIAUME , who performed in both Macbeth and Waiting for Godot this last season. This was Liam’s first professional contract, and he was remarkable in both shows, displaying tremendous wit, verve, and heart. In fact, the Winnipeg Free Press agrees with us wholeheartedly, featuring Liam’s performance as one of the stand-out moments of the year in critic Holly Harris’s piece: SHINING STAGE MOMENTS OF 2025 . We were so lucky to have him join SIR this year! Enjoy the conversation below: What inspired you to join Shakespeare in the Ruins as an actor? I was drawn to SIR for a couple of reasons, but of course one of the biggest pulls for me (as I’m sure it is for a lot of people) was the location! Getting to perform outside in the summer, in front of and inside the Ruins feels like being a kid again. I get to run around a “castle” with a sword and play with a bunch of people?! Who wouldn’t want that? Another big reason is getting to do Shakespeare with other people who love Shakespeare, and with actors whom I admire for their craft. It was an excellent way for me to get my foot in the door of the professional scene in Winnipeg. What is the most rewarding part of performing in the unique setting of the ruins? Thinking of this question my mind goes two directions. Firstly, from a more technical aspect as an actor, it really helped my voice. Having to run around the Ruins, jump into a scene, and then make sure people on the other end of the ruins can hear me through distant thunder and rain is the best kind of practical experience an actor can have. You can immediately tell when someone is straining to hear you on the other end, and it made me work hard to find a way to project safely without ruining my voice. The other direction my brain went was, as I mentioned in the previous question, getting to play outside. We had a great summer (if you don’t count the smoke) so getting to do something I love outside in front of an audience is such a treat. There were so many moments where having the elements to play with added to the experience for myself and for the audience, and that is truly special. Performing in the Ruins can be unpredictable—can you share a time when you and the team had to think on your feet to keep the magic alive? Towards the end of the run we had gotten some serious rain. At one point it had rained so much during the day that parts of the Ruins were full of ankle-deep puddles, and we couldn’t perform or have the audience sit in that. We had done blocking for a stationary run, but because it was an evening show we needed lights and all of the plugs that were available were in the flooded Ruins. Thankfully, the Technical Director Cari had the bright idea to drive her car up, so the headlights would shine into the area we would be performing. So we had to do this stationary run with minimal prep time and practice, and with only the lights from a car to light us for the end of the performance as the sun set. It was one of the more exciting and fresh runs we did because everything felt new and uncertain, which is something I think every actor should get to experience. Could you share what it was like to perform in both Macbeth and Waiting for Godot? How did those experiences differ for you? Tiring and rewarding. Both of the shows were so different from each other in terms of content, pacing, ideas, and character; but both were very demanding, especially at the start. With Macbeth, the action starts right from jump; we’re running around, yelling at each other, running again and then we’re onto the next scene and a different character. We kept that pace until we’re at the third location and then we get intermission, and the second half felt more calm for me. Fewer changes, less running, more stakes for the characters though, because of course we’re reaching the climax and we’re overcoming the tyrant Macbeth. On the flip side of this with Godot, once I got on stage a third into act one, I stood still with minimal shuffling for probably 40 minutes staring at one rock on the wall with my mouth hanging agape. At the end of my mental dissociation, I then have this mind boggling rant that is 5 minutes long where I hobble after the other characters, and once that’s done I don’t talk again for the rest of the show, but I am still present. One show is extremely high active energy and the other is extremely low active energy. With Godot I still had to be present as there were a lot of bits where I was yanked or had to shuffle and drop a bag, but I have to give the impression that there is no thought running through my head. Both of these were extremes for me, but so much fun. It was a marathon for both shows, but so rewarding to have these completely different experiences simultaneously. What did it mean to you to win the “Unexpected Phone Call Award” in memory of Glen Thompson? It was such an honour, and in all honestly completely unexpected. I had heard of the award before and knew people who had received it, but I wasn’t clear on the criteria of the award, so I wasn’t thinking I was in the running for it. When I heard we were going backstage to help give the award as a cast I thought that that was a fun idea, because I’d get to see who won it and how they reacted. You would have had to have been there to see the silliest grin plastering my face when they said my name in the phone call, but I couldn’t have been more honoured. To win an award that’s made after such a great actor is a real treat, and really helped me realize just how much I love the theatre community and the people in it. I never met Glen, but I heard others talk about him, and he is the reason the theatre community is so special, so to get the recognition of an award named after Glen is amazing and makes my heart feel very full for theatre and the people that make it happen. Why do you think it’s important for the community to protect and support Shakespeare in the Ruins? It’s important because small companies like SIR are where the heart of theatre lives. We get to have an intimate and touching experience with the audience that they can’t always get in other larger companies around the city. It’s a smaller crew, a smaller cast, and you get to see a show that has made people laugh or cry for more than 400 years. You get to learn about history, and see these characters that are so brilliantly written, so brilliantly that you can see yourself in them. It may sound romantic and overwrought but there is something so transfixing about the characters that Shakespeare writes, because most people can see parts of themselves in these characters and maybe understand actions they take, good or bad. Of course there is also a certain visceral nature to being outside with the actors, experiencing the heat, the rain, the thunder, that is unlike so many theatre experiences elsewhere. When you combine the writing of Shakespeare, the nature you’re surrounded by in the ruins, and the performances of some wonderful actors, you get to have a really magical experience with a community of other people.

December 17, 2025

As we continue to digest what a landmark and slightly bonkers year 2025 was for SIR, we caught up with Macbeth director EMMA WELHAM, who bravely survived the famed cursed play! Emma reminds me a lot of myself when I was starting out: passionate about the work, a true lover of the form, and an enthusiastic collaborator who lives and breathes for the joy of making words jump off the page and come alive. Directing Macbeth was her first professional contract as a director, and she talks about the importance of companies like SIR – a place where emerging talents get to shine and join the professional industry. – RODRIGO, artistic director ***** How is life now, Emma, after having survived a legendary season at SIR? What have you been up to? Life is grand at the moment! After the SIR season finished, I returned to Montreal to begin my final year in the directing program at The National Theatre School of Canada. At the time of writing this, I have just finished the fall term where I had numerous wonderful experiences including directing My Name is Lucy Barton as my capstone project, and spending two transformative weeks studying Shakespeare with Sir Gregory Doran, former artistic director of The Royal Shakespeare Company. Now I’m back in Winnipeg for the holidays and enjoying catching up with the community here. What attracted you to Macbeth, and why did you want to direct such a complex text? I wrote about this in my director’s notes – Macbeth holds a very special place in my heart because it was the first SIR show I ever saw! The stripped down tour came to my high school when I was in grade 11 and I’ve never forgotten the experience. Outside of those fond memories, I think Macbeth is a very timely show. I was attracted to its tale of how unchecked ambition can throw a whole society into turmoil. As well, the conversation the play raises on toxic masculinity and how, for me, it questions what happens when we shut ourselves off from our feminine side was extremely compelling. I also became fascinated by the relationship between Macbeth and Lady Macbeth – they start off as equals, and once Macbeth starts to shut out Lady M, charting how both of them unravel through this new found isolation was a delight to explore with the actors. Finally, it was a very exciting challenge to examine and explore all the possibilities that were opened up to us because we were staging Macbeth at the Ruins! What do you think are the biggest challenges of directing at the Ruins? When you work at the Ruins, because you’re outdoors, every day comes with unknown variables and you have to be prepared for many possibilities. For example, you might plan to spend all day blocking, but if, suddenly, a massive storm comes, you’ve got to be able to change plans real quick. I don’t think I’ve ever checked my weather app more than when I’ve worked at the Ruins! I also echo what others have said, in that I think climate change is becoming an increasingly difficult challenge for not just the Ruins, but for all outdoor theatre. Even comparing my experience working on The Dark Lady in 2023 to Macbeth in 2025, in just two years there has been a massive increase of shows cancelled due to smoke and storms. It’s heartbreaking. And the best things? Things you can only do and experience at SIR? I love working at the Ruins. Out there in nature with the team, feeling slightly removed from regular life, I always feel like I’m away at summer camp. SIR allows you to create a theatrical experience unlike anything else in Winnipeg. The whole site is really your playground, and you can create these sweeping moments that engulf the audience and immerse them in the story. The promenade nature and the fact that you can see the audience for the majority of the show also enlivens that bond between performer and audience in a unique way – it becomes very intimate. Especially in Shakespeare, with all his soliloquies, the audience really becomes a collection of people that the characters can turn to and bare their souls. As well, while all theatre offers a sense of liveness, of anything-can-happenness, at the Ruins I find that liveness heightened because TRULY anything can happen – Will you see wildlife? Will the weather create a perfect atmosphere for the climax of the play? Will a rock calypso band be playing next door? (All real examples of things that I have experienced at the Ruins.) It is always an unforgettable night of theatre. What are some of your fondest memories of enduring Macbeth? During the process, did you ever wish you were directing another Shakespeare play? Perhaps a comedy? I have many! First, I have to say the resilience and unwavering dedication of everyone, from the cast and crew to the full-time SIR staff as we took on everything this season threw at us will always inspire me. In terms of specific memories, I will name the following two: 1. Before the show opened to the general public, we had several student matinees – seeing them engrossed in and reacting to the story was a true highlight. 2. Our witches were crafted around birds, with their costumes being inspired by owls. And when we got out to the Ruins, we had two majestic owls who joined us and could often be seen and heard. What’s more, these owls are barred owls (pronounced bard) – we had our very own Shakespeare owls! To answer your second question, no, I never wished I was directing a different Shakespeare play while doing Macbeth. However, as we worked, I did get flashes of how I might do other Shakespeare plays out at the Ruins – there are several I’d love to do out there! When one of the actors fell sick, about 3 weeks into the run of the show, you were called upon to perform in their place, book-in-hand. How was that?! Did it make you want to act again? Was it very different experiencing the play from inside? It was an exhilarating experience! The last time I had performed Shakespeare was in a 2019 production of Love’s Labour’s Lost directed by Rodrigo (which is how we met, and this wonderful journey began), so to be able to stretch those muscles again was a challenge I had a lot of fun meeting. And it must be said how incredibly supportive the entire team was – from gently nudging me where I needed to go, to helping me learn fight choreo before curtain, to cheering me on through-out – it was a beautiful thing to know I was amongst people who always had my back. What I loved experiencing from the inside was getting to see all the intricacies of everything going on backstage, some of which I was aware of, and some of which I was not, that allowed the show to run smoothly, and which I never saw while watching the show from out front. Also, I will say: it was 28 degrees and sunny the day I went on, and by the time we got to act 5, I had gained a deep appreciation for the stamina it takes to do a show in those weather conditions! I don’t know if I’ll act again (I’ll never say never!), but I certainly will remember my SIR acting debut for the rest of my life! Why do you think it’s important to protect the future of a company like SIR? SIR is a vital part of not just our theatre community, but our Winnipeg community. From an artistic stand-point SIR not only allows artists to sink their teeth into these beautiful heightened texts, but also gives many emerging artists, myself included, some of their first professional opportunities, allowing them to grow by working alongside and learning from the immense talent we have in Winnipeg. From a community stand-point, there is no theatrical experience in Winnipeg like what you experience when you go to a show at the Ruins. To me it has always felt like stepping into another world. And finally, what’s a favourite play by Shakespeare you’d love to direct one day? My favourite play by Shakespeare is Much Ado About Nothing. A long-time lover of the Kenneth Branagh film, that’s a show I very much hope is in my future as a director! ***** PS. IF YOU HAVEN’T YET, PLEASE CONSIDER A DONATION, AND PROTECT WHAT YOU LOVE: YOUR SHAKESPEAREAN COMPANY, SIR!

December 6, 2025

The incredible Cari Simpson, SIR’s Technical Director and all around crew magician, reflects on her time with the company, overcoming the challenges of the great outdoors, and the importance of protecting our unique theatrical practice: I first started working with SIR for purely practical reasons; on my end it filled a gap in my work schedule before Fringe started up, and on the company’s end the shows had started getting so large and complex that the actors couldn’t do everything themselves anymore like they used to. They had hired Steve Vande Vyvere on as crew a couple years before that to help with the workload, and when he took over as PM (production manager), the shows had grown even more on their return to the Ruins in 2012 that he brought me on for extra help. After my first show, which was Comedy of Errors (2014), I was hooked and immediately let Steve know I wanted to come back next year. It was a like a weird chaotic summer camp; I was dressed in a costume, pulling the old sound system around on a wagon, and dragging a crash mat from window to window for the actors to jump onto. In most theatre jobs, you spend your days inside, in my case often in a dark booth, so the change each spring to the fresh air and beautiful sunsets and wildlife running around is a nice way to balance my year out. And the actors and crew that think “yeah, I want to spend 2 months being outside, sometimes for 12 hour days, in all kinds of weather,” are my kind of people. There’s always a great camaraderie among everyone out there, and I’ve added a few truly close friends to my life from my time at the Ruins. That’s what keeps me coming back every year. I mentioned Comedy of Errors was my first mainstage show with the company, so it’s been 11 years now! The biggest change I’ve seen in my time with SIR is sadly the climate crisis and its effects on everything. Wildfire smoke is a new challenge from the last couple of years for sure, but the biggest hurdle is the storms. When I first started, we would regularly move under our giant tent if the rain was too bad to continue performing outside, and we would only cancel for the occasional thunderstorm. Now it’s almost the reverse, we so rarely have rain that isn’t part of a storm system, our eyes are always glued to the radar watching for lightning strikes to get too close. That’s why we sold off the tent; we had 2 years in a row where we basically couldn’t use it because you can’t tell the audience to go stand beside a giant metal tent pole in a lightning storm. It used to be fun to occasionally watch the actors speed through the last scene to finish a show just before the rain hit, but now we spend at least a third of the shows just wondering if we’ll make it to the end at all. I think the most rewarding part of doing shows at the Ruins is being so close to the audience . You can feel their reactions so much more than from a booth, and lots of people come up to talk after and say how much fun they had, or that this was their first theatre show ever! There was a man last year who told us he comes up from the States every year to visit family and times it so that he can see our shows. It’s always just great watching people have fun. The biggest challenge of doing shows at the Ruins is trying to be prepared for as many strange circumstances as possible. Steve had to go wade in the river after a pup tent that blew away in R&J, squirrels have wandered into scenes and stolen props, and one year we had a pilot flying training loops over the Ruins and drowning out the actors. Last year, we had our first storm cause power outage, which meant we couldn’t use our work-lights to light the sword fight scene for safety. In Richard III, we had lit the final scene with the headlights from the limo that was in the show, so I pulled a leaf from that book, drove my car up on the grass, and hoped I wasn’t going to kill the battery (thankfully it didn’t). No two performances in the run are ever the same out there, so trying to be prepared for all eventualities really keeps us on our toes. I think we need to protect SIR for it’s wonderful uniqueness . The beautiful interplay between the show and the nature of the park is something I feel just can’t be found anywhere else in the city. The Ruins truly are a setting and a character in every play we do, and for people to lose the opportunity to come experience the beauty of a performance in that space would be heartbreaking. Please support SIR if you can! – Cari Simpson, SIR Technical Director, Running Crew & Jedi

November 30, 2025

Recently, I had the good fortune of sitting down with Arne MacPherson over coffee to talk about his work with Shakespeare in the Ruins. I first met Arne many moons ago when he was the instructor for a directing course I took at Prairie Theatre Exchange. Since then, he has been someone I deeply admire, a true pillar of Winnipeg’s theatre community whose legacy I greatly respect. As a founding member of Shakespeare in the Ruins and now a dedicated board member, Arne brings a wealth of experience and insight. That connection gave me the perfect opportunity to ask him about the origins of the company, his most memorable roles, and why it’s so important to protect what you love, especially when it comes to preserving unique cultural experiences for future generations. ***** Adam : As one of the founding members of Shakespeare in the Ruins, what inspired you to help create this company, and what does it mean to you today? That’s kind of two questions. Arne : Well, the legend goes, memory is selective and unreliable, but the story is that Lora Schroeder, Deb Patterson and I were out at an event at the Ruins in St. Norbert. I think it was Lora who had the idea: Wouldn’t it be great to do Romeo and Juliet here? That was the spark. The site had never been used for theatre before, and we thought, That’s a great idea. So, the first impulse was the site. The second was Shakespeare, specifically Romeo and Juliet. When we started planning, we decided to create a co-op so there was a sense of collective ownership. We stayed a co-op for over ten years until the organization grew, and we realized we needed a board of directors. Structurally, a co-op didn’t make sense anymore. So, we shifted to the structure we have now: an artistic director, a general manager, and a board. But at the beginning, there was a real ethic of collective effort. Those were the three impulses at the start. Today, I’m much less involved, mostly as an audience member for quite a while. For me now, it’s all about the site: doing theatre in that space. For example, this year I didn’t do Shakespeare, I did Waiting for Godot. I love that the company’s scale is friendly, the staff isn’t too big, and the personality of the company is easy to access. I really like that. I prefer it to working in big institutions. So, for me, it’s the size of the company and the place where we do it. Adam : So last season you performed Waiting for Godot. What was that experience like? And do you have any memorable roles over the years that stand out? Arne : Waiting for Godot was a hit, top three of my time at Shakespeare in the Ruins, maybe top three ever. The experience was incredible: the quality of the script, the company of actors, the direction, and the way the play worked in the ruins in a way you could never recreate in a traditional theatre. I’ve been lucky to play some of the great roles, Hamlet, Richard III way back in the late ’90s. Malvolio in Twelfth Night was big fun. Even lesser-known ones, like Don Armado in Love’s Labour’s Lost, were a blast. Adam : If you could revisit one role today and do it all over again, which would you choose? Arne : Oh, I wouldn’t play Richard III again, nobody who’s able-bodied should play that part. That was a thing of its time. Honestly, every production was what it was. Revisiting a role means revisiting the whole play with a different director, a different time, and a different world. I’m different now, physically. I wouldn’t want to play Hamlet again; Hamlet shouldn’t be a 60-something-year-old guy. So, I’m happy with all those experiences as they unfolded. Adam : If you could go back and talk to Arne, Lora, and Debbie when you started the company, what would be the most surprising thing about where Shakespeare in the Ruins is today? Arne : First of all, none of us would have imagined it lasting three years, let alone thirty-five. The fact that it exists and has become such an important part of Winnipeg’s cultural ecology is something we never could have predicted. I think it would surprise young Lora, Deb, and Arne that it’s not a co-op anymore. The company has grown into a very functional, efficient organization. Adam : And my last question: Why do you believe it’s important for the community to protect and support Shakespeare in the Ruins for future generations? Arne : All you have to do is talk to an audience member about how special the experience is. It’s unique. It’s like saying, we don’t need the Winnipeg Folk Festival because you can go to the Concert Hall. Sure, you can hear music elsewhere, but it’s not the same. Shakespeare in the Ruins offers an experience people cherish. If it disappeared, it would be a real loss. It’s the only theatre in Winnipeg that creates work outdoors, in the real environment. And beyond that, it’s in an incredible setting, with promenade staging. It’s unique, and people value it deeply. ***** After I stopped recording, Arne continued to share fascinating details about Shakespeare in the Ruins’ early days. For instance, after some productions, the company would serve food to the audience, a gesture that speaks to the intimacy and community spirit of those beginnings. He also told me that in the first few seasons, there wasn’t a full production team. There was just a stage manager, which meant the actors and team members themselves were responsible for laundering costumes, building props, and creating sets. One of my favorite stories was about the journeys audiences used to take during performances. In The Tempest, for example, the audience would walk down by the waters, swatting away mosquitoes, to encounter characters in unexpected places. Arne described how, instead of seeing Ferdinand chopping wood, audiences found him breaking boulders, a striking image that captures the immersive and adventurous nature of theatre in the ruins. These stories remind us that Shakespeare in the Ruins has always been about more than just theatre. It is about creativity, resilience, and a deep connection between artists, audiences, and the land. To keep that spirit alive, we must protect what you love, because experiences like this are rare, and losing them would be a true cultural loss. Adam Jennings , managing director SIR PS. PLEASE CONSIDER A DONATION , AND PROTECT WHAT YOU LOVE: YOUR SHAKESPEAREAN COMPANY, SIR!